What do you see?

Deserts...lions, giraffes, elephants roaming across grasslands...sparse vegetation, perhaps?

|

| A typical image conjured in one's mind of Africa? (Source) |

|

| The alternative, perhaps overlooked perspectives of Africa (Sources: top left, top right, bottom) |

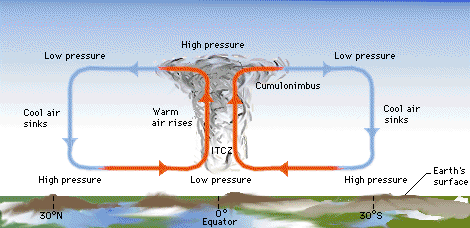

Africa straddles the equator, and its climate is largely determined by movement of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ). This band is situated between two large atmospheric overturning circulations in either hemisphere: the Hadley Cells. These are driven by the differential heating of the planet. Where solar radiation concentrates at the equator, warm, moist air is forced to rise. As air rises and starts moving polewards, it cools and loses moisture, bringing seasonal rain to the tropics. The dry, cooler air then sinks, creating high pressure at the subtropics, which consequently forms 'Subtropical Dry Zones', where Earth's major deserts are found.

|

| The Hadley Circulation and formation of the ITCZ between the two cells (Source) |

This large low pressure rain band doesn't stay put for long, migrating south of the equator during the Northern Hemisphere (NH) winter, and shifting north of the equator during NH summer. African countries sitting between the ITCZ's annual path are blessed with rain throughout much of the year (e.g. Democratic Republic of Congo). However, countries which only greet the ITCZ once a year (e.g. Sudan) have just one deluge. Put simply, countries lying between the ITCZ's extent of movement are generally humid, and countries outside of that area are semi-arid or arid. The ITCZ is therefore vital in controlling the temporal and spatial distribution of precipitation across the continent.

|

| Annual migration of the ITCZ (Source) |

Global climate change is a very real and imminent threat to Africa's population, ecosystems and water resources (Carter and Parker 2009). Evidence is constantly growing to show anthropogenic warming has increased over the last century, particularly over parts of the arid African continent, where surface temperatures have risen by 0.5°C in the last 50-100 years (Niang et al 2014). The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Fifth Assessment Report (AR5) suggests that towards the end of this century heat waves will increase, droughts will intensify, and extreme precipitation events will become more common (Niang et al 2014). Under a high emissions scenario (RCP 8.5) it is possible that Africa could warm by 3-6°C by the end of the 21st century (Niang et al 2014)! A temperature rise of that magnitude, though uncertain in probability, would seriously exacerbate existing water stresses.

The Clausius-Clapeyron relation demonstrates that as temperatures rise in a warmer world, the atmosphere can hold more moisture, hence the global hydrological cycle will intensify. Durack et al (2012) predict this intensification could be as much as 24% in a world warmed by 2-3°C. This would mean more extreme heavy downpour events, with fewer low-medium intensity events (Allan and Soden 2008). The general rule of thumb is the 'wet gets wetter, and the dry gets drier'. Dry North and Southern Africa are predicted to experience reduced rainfall, whilst relatively humid West and East Africa may experience more intense wet seasons (Niang et al 2014). For countries like South Africa, climate change could cause the loss of perennial (year round) water supply (de Wit and Stankiewicz 2006). Regional and local aspects of climate change in Africa mustn't be overlooked - hydroclimatic changes are not uniform across the continent!

There are MANY more consequences of climate change on various water resources in Africa that cannot be covered in this one introductory post. This is just the tip of the iceberg (excuse the pun). For now, it is important to recognise that climate change threatens to disrupt the rhythm African people have become accustomed to. Entire livelihoods can be based on one seasonal flood. If that flood doesn't happen in a warmer, uncertain future, crops will fail, livestock will starve, farmers will lose money, and Africa's taps might just run dry.

For more in depth information and a really good insight into climate change and policy in Africa, I recommend reading Chapter 22: Africa, in the IPCC's AR5 WG2 report - aka Niang et al (2014).

The dark continent,as it was once called,is indeed in danger of becoming even darker.I wonder whether it is accurate to use Africa as a model for what might happen over the rest of the continents,Katy.

ReplyDeleteHi Katy, such an interesting post!

ReplyDeleteClimate change is going to be such a huge challenge for Africa. A continent so diverse and heterogenous is going to be affected in so many different ways, it will be a mammoth task merely for science to keep track, let alone suggest tactics for combating this theat!

Hi Joe, thanks for your comment! I agree, there will be many obstacles to overcome in the near-future that will need contributions from governments at the top, and small-scale farmers (for example) at the bottom.

Delete